Author: S Chadalavada

Case Summary

An interesting case of a 27-year-old male with a rare homozygous splice mutation which led to ESRF and kidney transplant at age of 21. The congenital condition also led to complex LV outflow obstruction with a fibromuscular shelf and fibrosis extending to native aortic valve and MV apparatus. This required myectomy aged 10 and mechanical AVR and MVR and repeat sub-aortic myomectomy aged 20. While clinically stable, and asymptomatic on warfarin and tacrolimus, was noted to have high gradients across mitral valve on follow up echocardiography. Therefore, a TOE was requested.

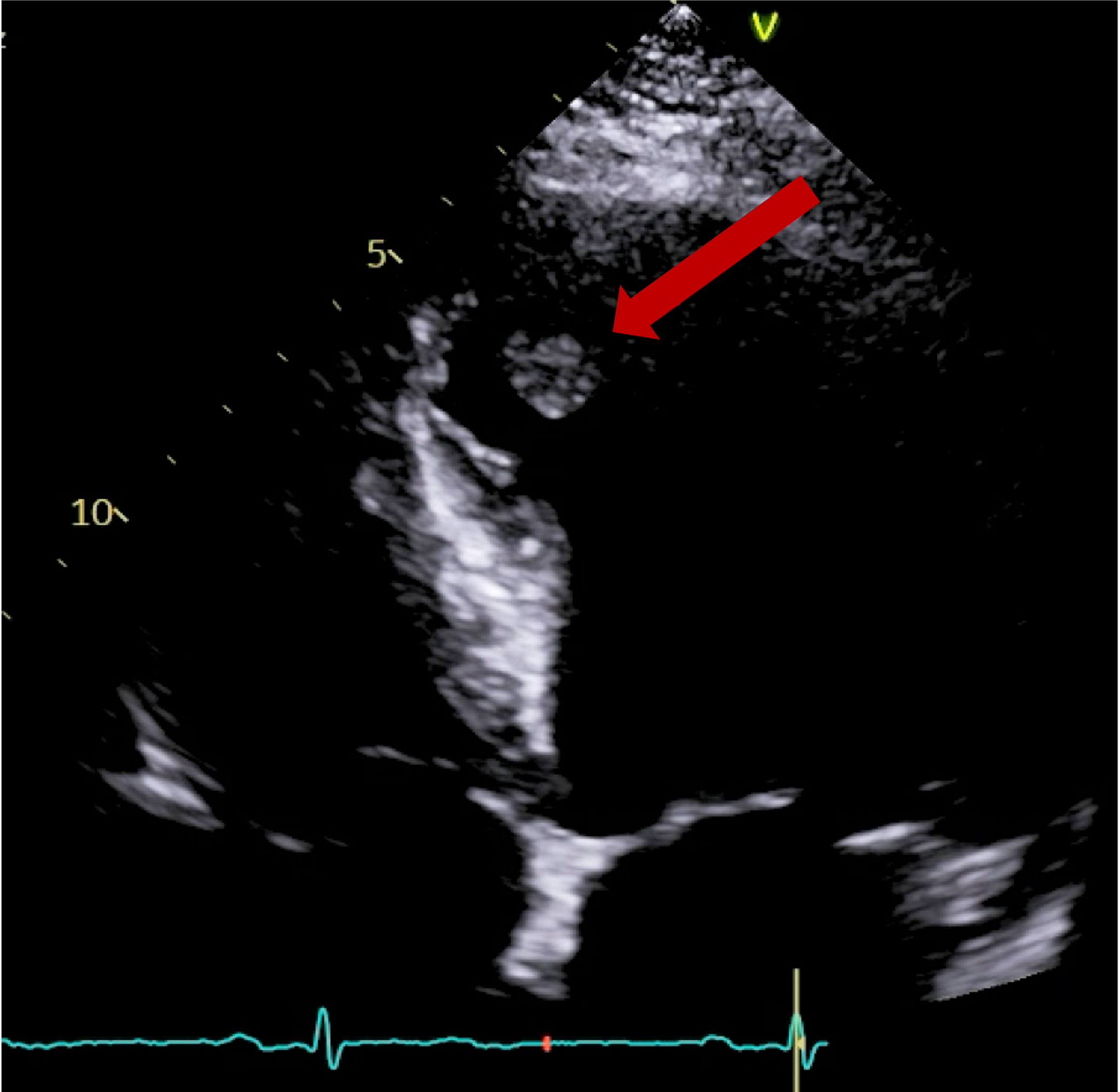

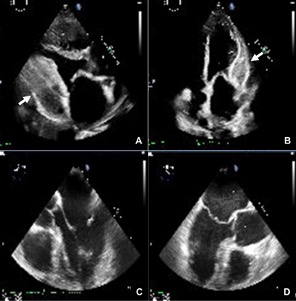

Impression from TOE:

- Posterior leaflet appears fixed with strands of fibrinous material ?thrombus.

- AMVL is seen to move normally.

- Significantly raised gradients 17mmHg across MV (context of tachycardia, HR: 108).

- Mild – moderate transvalvular MR.

Cardiac CT requested to understand valves better.

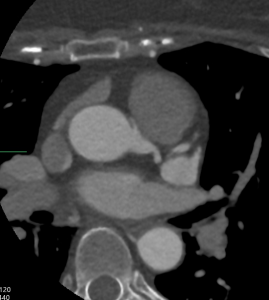

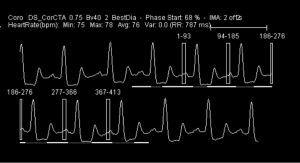

Retrospective CTCA performed with 10mg IV metoprolol given as preparation.

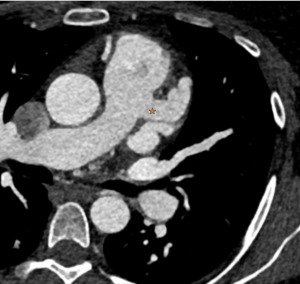

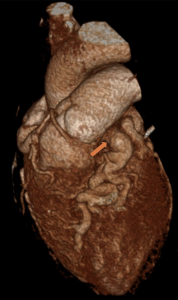

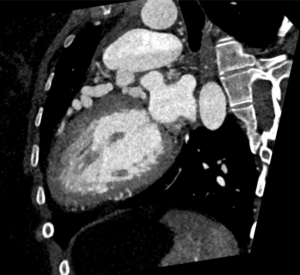

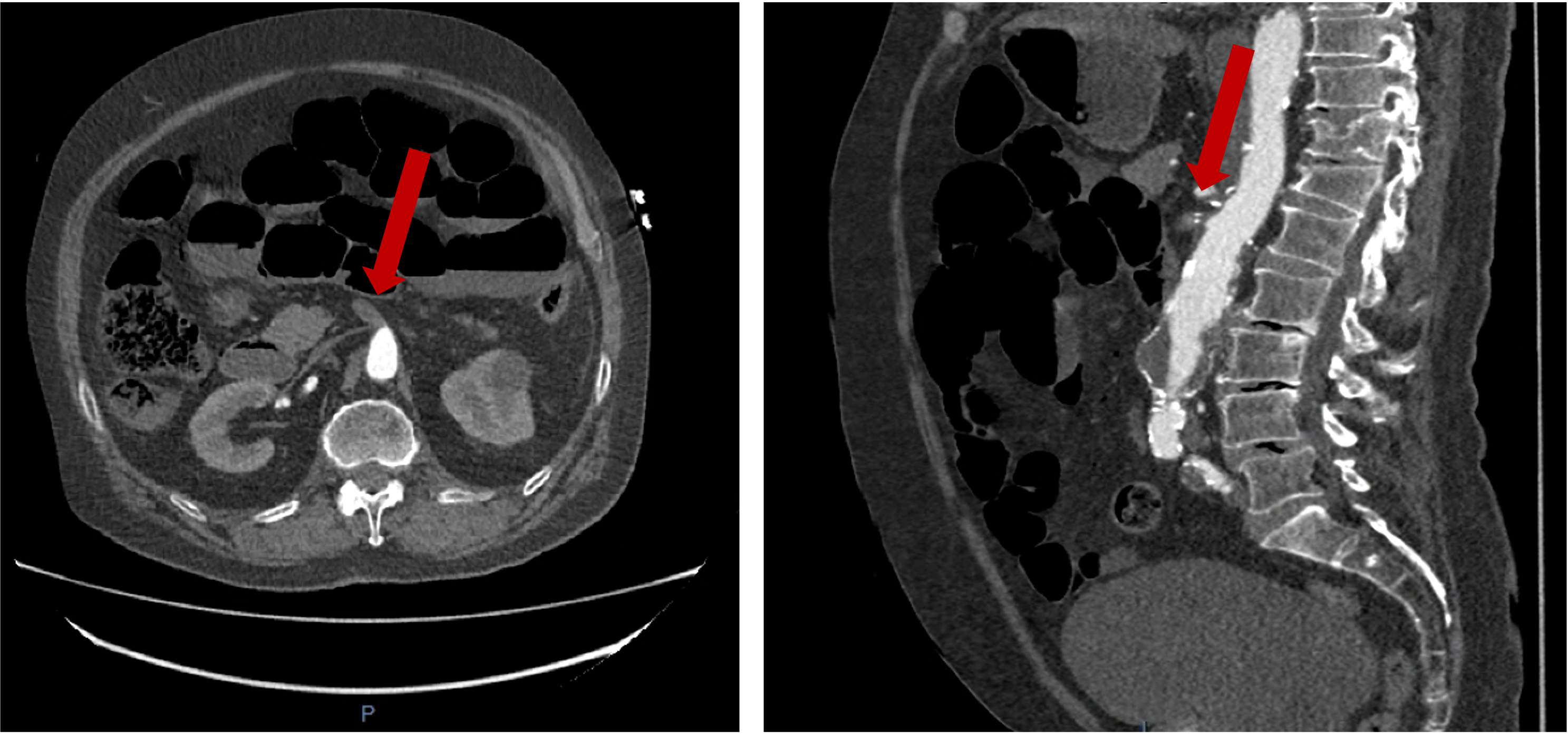

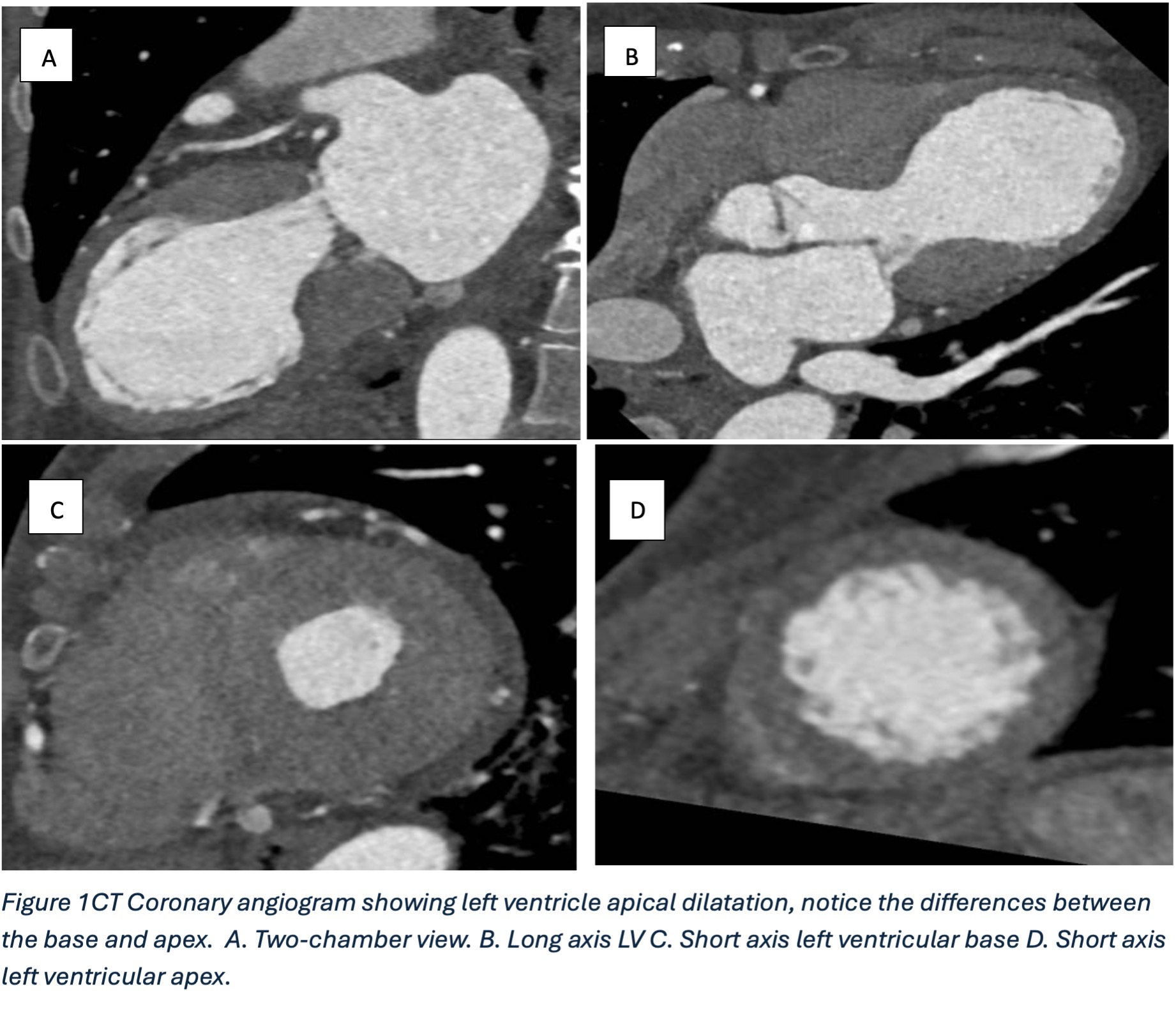

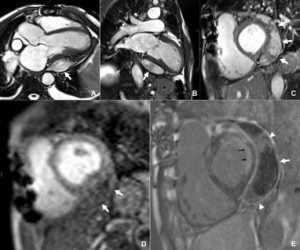

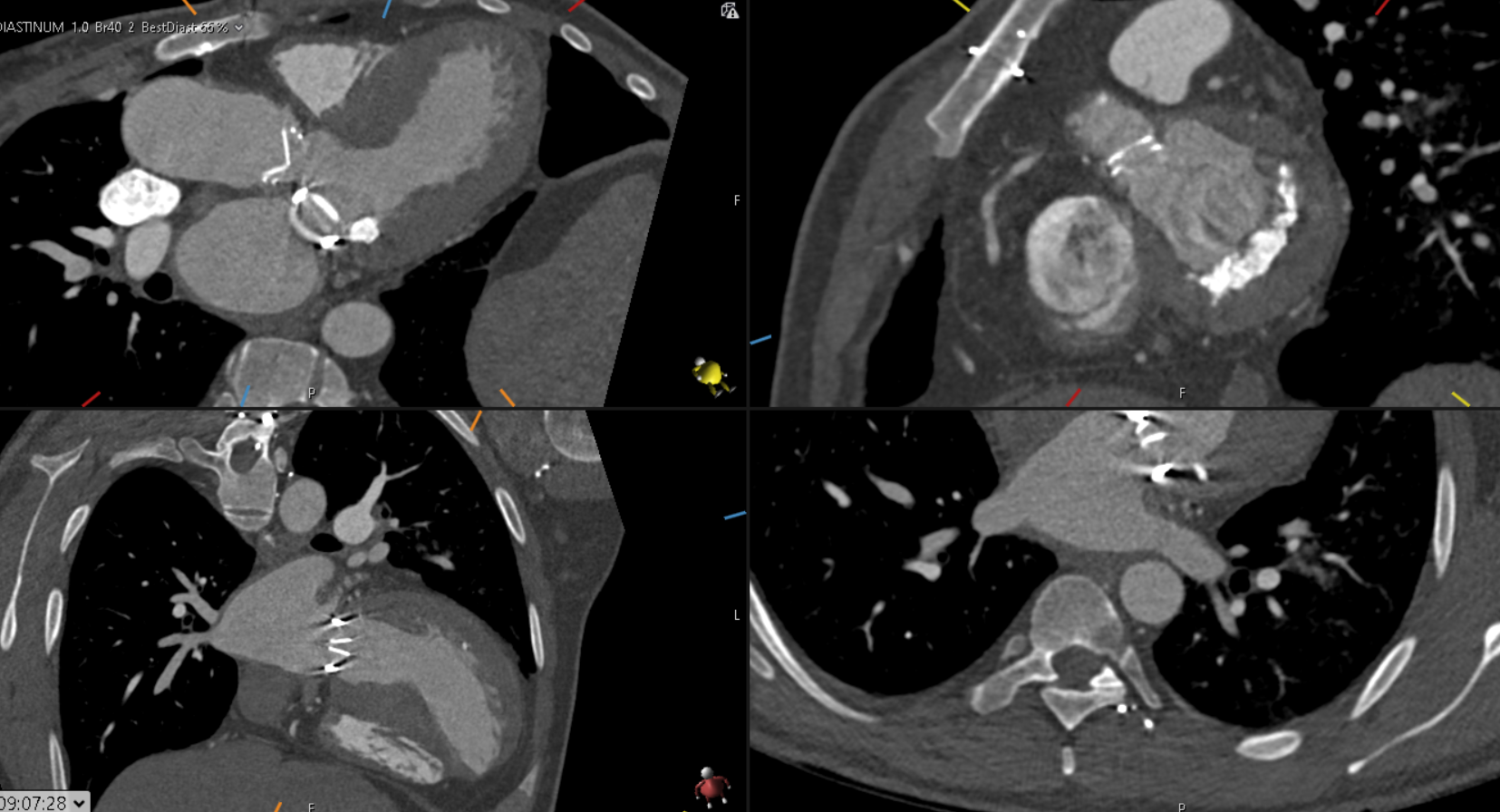

CTCA first highlights significant calcification around the mitral valve annulus not apparent on the TOE (Multi-planar reconstructions shown in Figures 1 – 3)

Figure 1

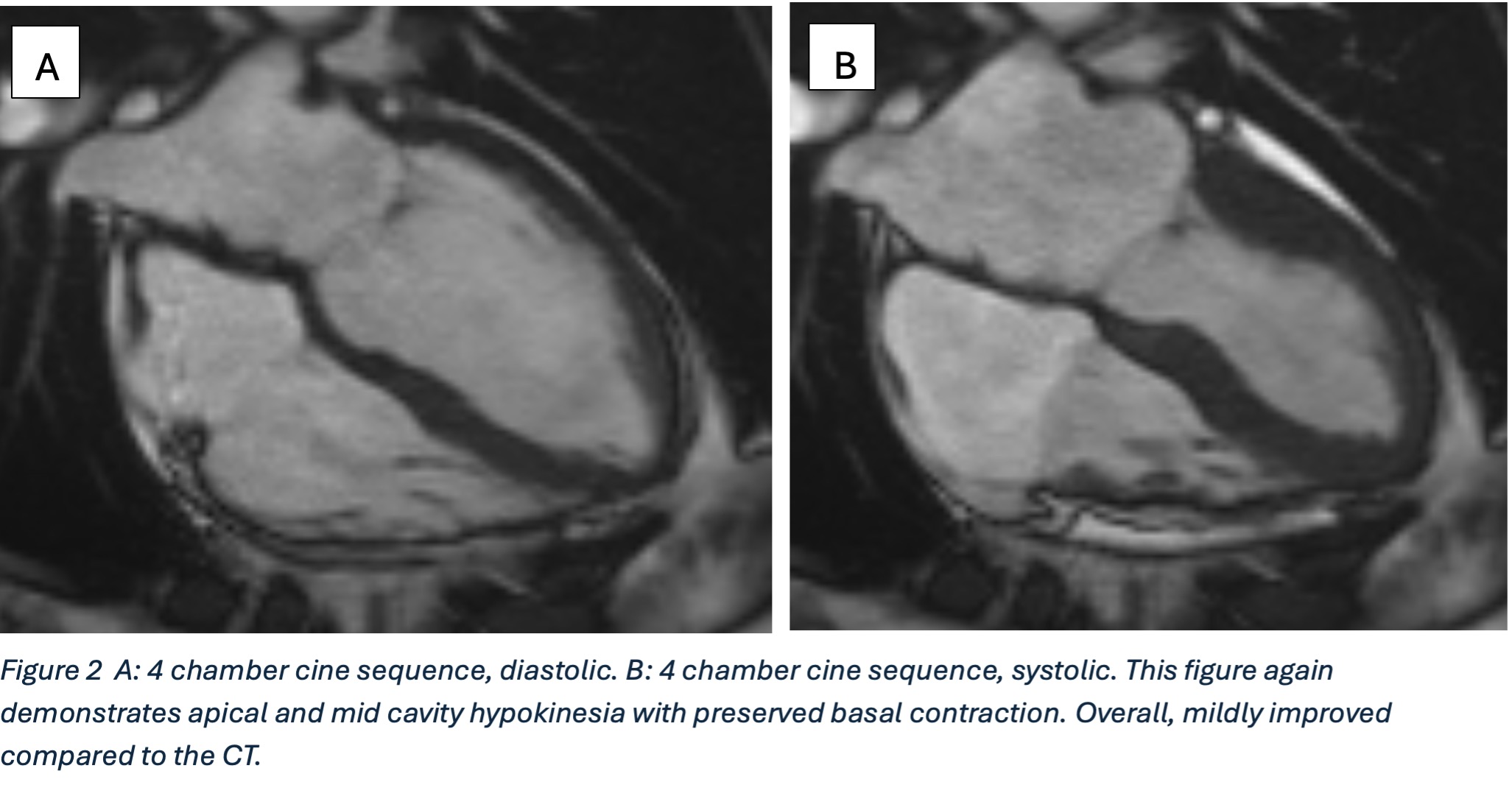

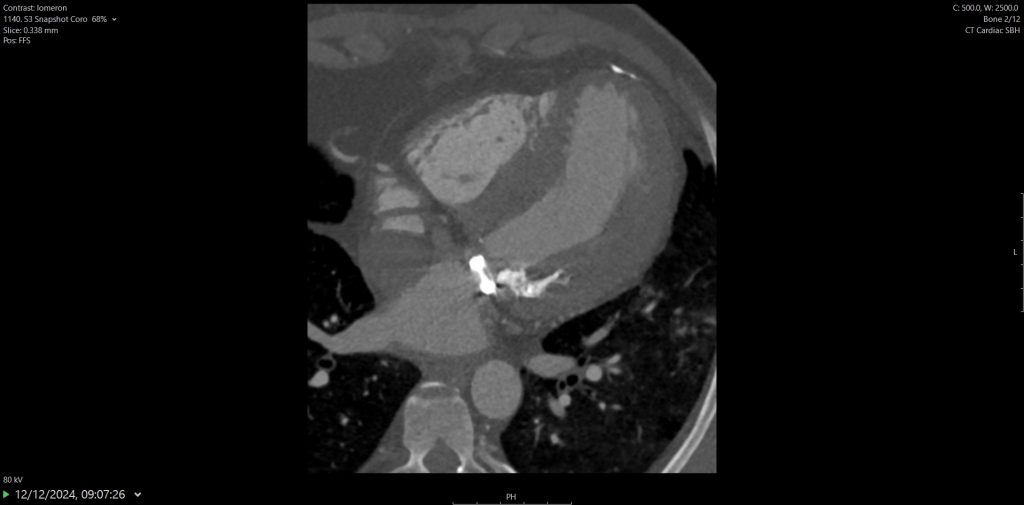

Figure 2

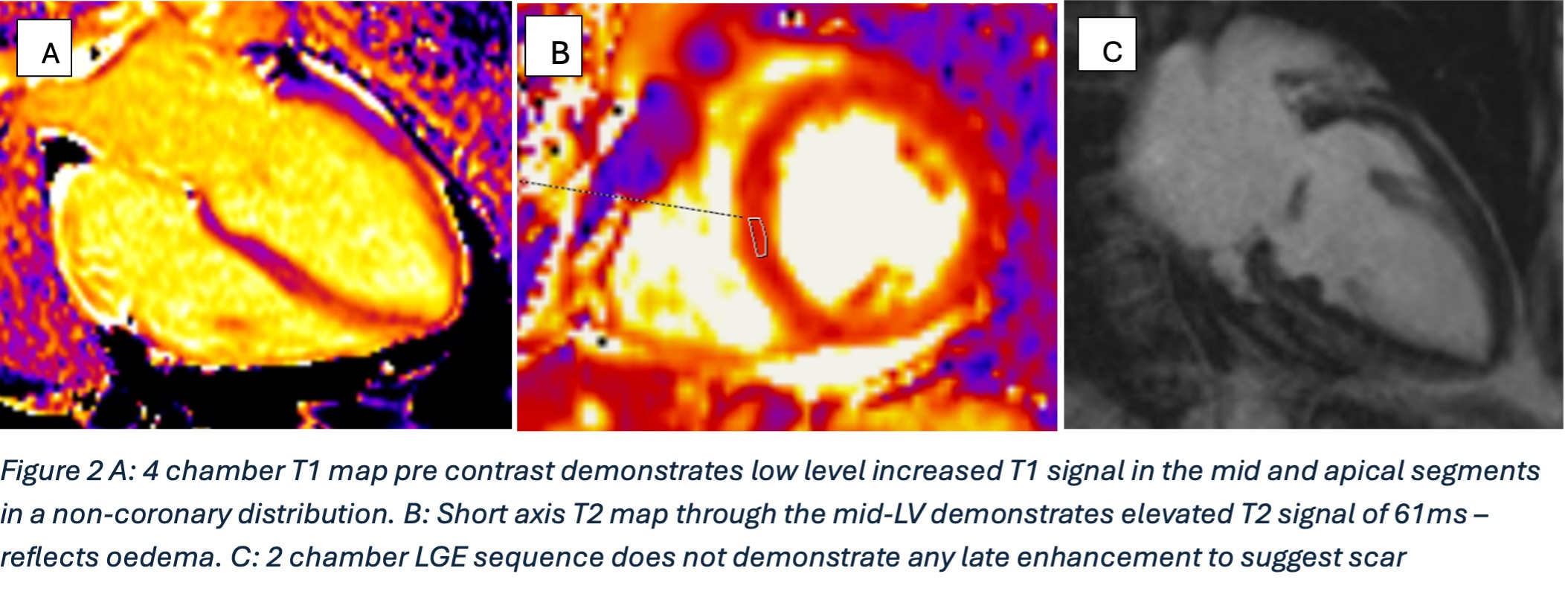

Figure 3

Further postprocessing using tools on cardiac function and reconstruction modules built-in the vendor software (Syngo.via) were used to produce anatomical depictions and cines of both valves. Valve cines showed valves seen to open and close normally. No pannus/ thrombus.

CT scan informed MDT decision, which were reassured that the valve is opening and closing normally. Increased warfarin range to 2.5 – 3.5 to avoid possibility of thrombus. Under regular follow up with serial echocardiograms.

Not the end of the story……

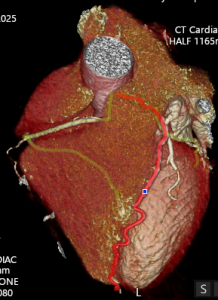

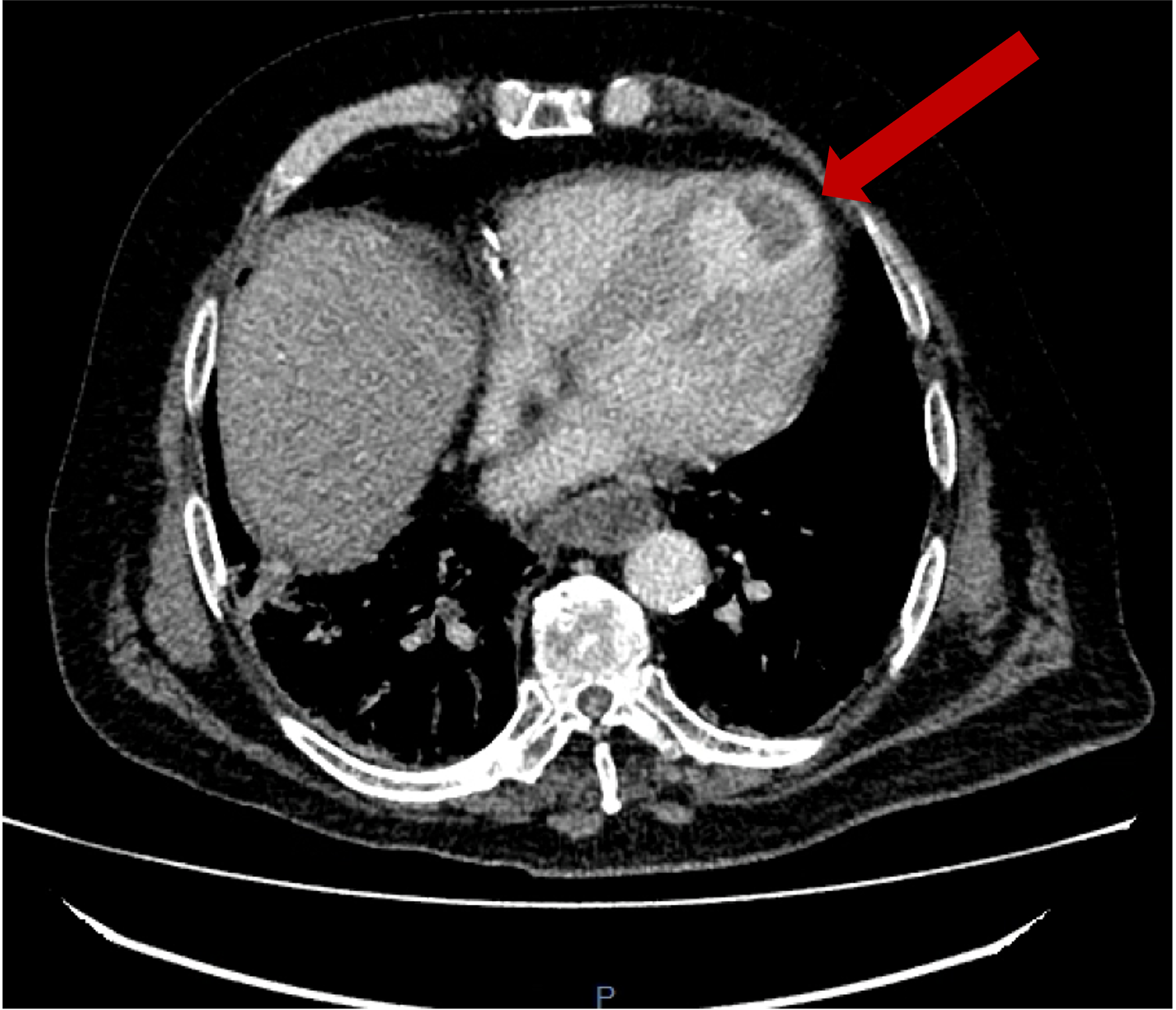

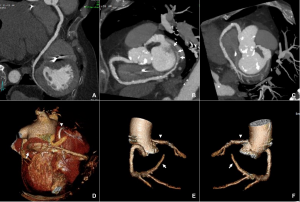

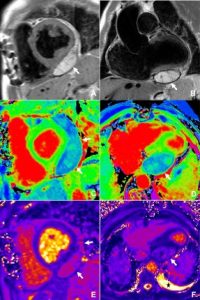

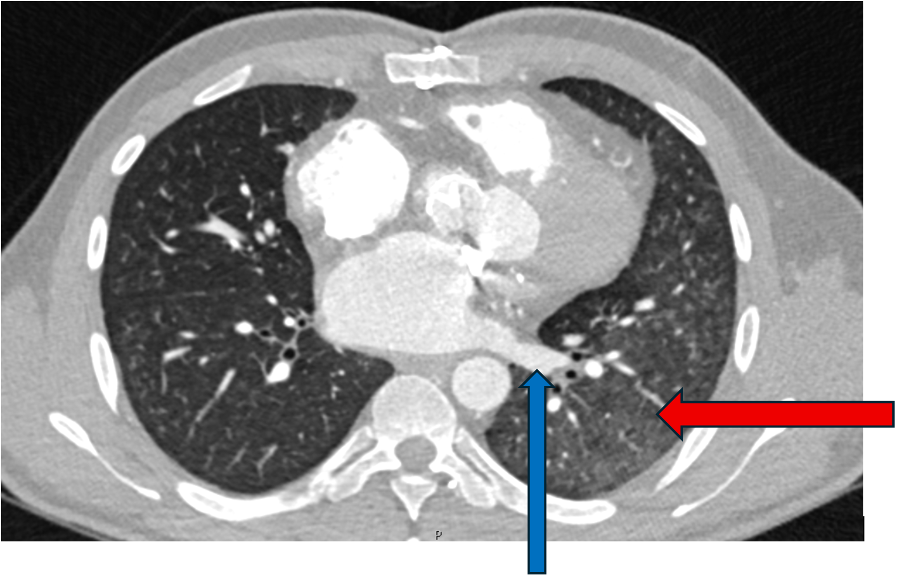

Figure 4

Lung imaging on cardiac CT showed left-sided asymmetrical pulmonary oedema (see red arrow).

This is a very rare presentation thought to be due to congestion in the common left pulmonary vein (blue arrow) secondary to turbulent blood flow around the posterior mitral valve leaflet.

Discussion:

Use of CT to assess valves (especially prosthetic) is supported as an adjunct imaging modality when echo is not able to assess fully (acoustic shadowing can impact image quality in echo). Radiation is a concern but can be limited by controlling HR (when appropriate) and dose modulation. Photon counting scanners coming online can potentially improve further.

Quiz:

- Which of the following is a recognised advantage of cardiac CT cine reconstructions in evaluating suspected prosthetic valve obstruction?

A. They can quantify mitral valve mean gradient more accurately than Doppler

B. They demonstrate dynamic leaflet motion throughout the cardiac cycle despite prosthesis-related ultrasound artefact

C. They eliminate the need for TOE in all patients with suspected valve thrombosis

D. They provide better assessment of valvular regurgitation direction than colour Doppler

2. When evaluating suspected prosthetic valve obstruction on cardiac CT, which imaging characteristic helps distinguish pannus from thrombus?

A. Thrombus typically has higher CT attenuation (Hounsfield units) than pannus

B. Pannus usually appears as a low-attenuation mass without leaflet restriction

C. Pannus demonstrates higher attenuation and is more fibrotic, whereas thrombus is lower-attenuation and may be mobile

D. Both pannus and thrombus have identical attenuation and must be diagnosed surgically

Answers and explanation:

1 – B –

Cine CT allows visualisation of valve leaflet motion frame-by-frame, even when echocardiography is limited by metallic artefact or acoustic shadowing. This makes CT particularly helpful in differentiating restricted mechanical leaflet motion from normal function, and in identifying pannus vs. thrombus.

2 – C –

On cardiac CT:

- Pannus is dense, fibrotic, and fixed, showing higher attenuation (≈ >145 HU).

- Thrombus is typically lower attenuation (≈ <90 HU) and may be more soft and mobile.

CT is therefore especially helpful when echo cannot clearly differentiate the two due to acoustic shadowing.

References:

- 2021 ESC/ EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Alec Vahanian, Friedhelm Beyersdorf, Fabien Praz, Milan Milojevic, Stephan Baldus, Johann Bauersachs, Davide Capodanno, Lenard Conradi, Michele De Bonis, Ruggero De Paulis, Victoria Delgado, Nick Freemantle, Martine Gilard, Kristina H Haugaa, Anders Jeppsson, Peter Jüni, Luc Pierard, Bernard D Prendergast, J Rafael Sádaba, Christophe Tribouilloy, Wojtek Wojakowski, ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group , ESC National Cardiac Societies , 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease: Developed by the Task Force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), European Heart Journal, Volume 43, Issue 7, 14 February 2022, Pages 561–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

- 2024 ACC/ AHA Guidelines for valve disease. Jneid H, Chikwe J, Arnold SV, Bonow RO, Bradley SM, Chen EP, Diekemper RL, Fugar S, Johnston DR, Kumbhani DJ, Mehran R, Misra A, Patel MR, Sweis RN, Szerlip M. 2024 ACC/AHA clinical performance and quality measures for adults with valvular and structural heart disease: A report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Performance Measures. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2024 Apr;17(4):e000129. doi:10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000129

- Schnyder PA, Sarraj AM, Duvoisin BE, et al. Pulmonary edema associated with mitral regurgitation: prevalence of predominant involvement of the right upper lobe. https://doi.org/102214/ajr16118517316. American Public Health Association; 2013;161(1):33–36. doi: 10.2214/AJR.161.1.8517316.

- Woolley K, Stark P. Pulmonary Parenchymal Manifestations of Mitral Valve Disease1. https://doi.org/101148/radiographics194.g99jl10965. Radiological Society of North America ; 1999;19(4):965–972. doi: 10.1148/RADIOGRAPHICS.19.4.G99JL10965.

- Rice J, Roth SL, Rossoff LJ. An unusual case of left upper lobe pulmonary edema. Chest. American College of Chest Physicians; 1998;114(1):328–330. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.1.328.