The natural course of an incidentally detected coronary artery to pulmonary arterial fistula

Author:

Dr Chary Duraikannu, Consultant Radiologist

Affiliations:

Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Clinical history and image findings:

A 68-year-old male non-smoker with a prior history of hypercholesterolemia presents with atypical left side chest pain. Recent ECG shows sinus rhythm, with an occasional ventricular ectopic. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), done four months prior revealed good left ventricular function with mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. The patient was referred for CT coronary angiogram (CTCA) to rule out any significant coronary artery disease.

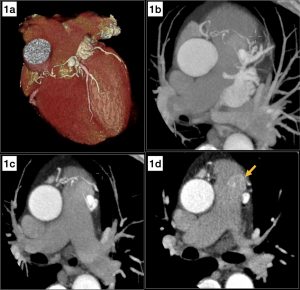

CTCA showed a bilobed aneurysmal sac (16 x 10 mm) adjoining the left side of the main pulmonary trunk, with a single large feeder from right coronary artery (likely conus branch) and multiple feeders from left anterior descending artery (Fig 1a-c). A blot of contrast density seen in the main pulmonary artery (yellow arrow) suggests the draining site (Fig 1d). The above findings were typical of a coronary artery to pulmonary artery fistula with feeders from the right and left circulation, forming an aneurysmal sac. The coronary arteries were free from atherosclerotic plaques with no significant coronary stenosis.

Fig 1. Volume rendering (1a) and axial thick MIP (1b,c) shows an aneurysmal sac adjoining the main pulmonary trunk with feeders from the right coronary and left anterior descending arteries. Axial image (1d) shows a blot of increased contrast density in the pulmonary trunk (yellow arrow) suggesting the drainage site.

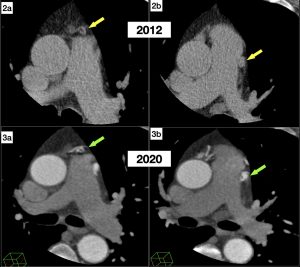

Approximately eight years prior (March 2012), the patient underwent calcium scoring, which was 0. Retrospective analysis of the images revealed a similar aneurysmal sac close to the main pulmonary trunk with adjoining feeding vessels (Fig 2,3). Despite the non-contrast scan, the findings resembled the present contrast-enhanced CT coronary angiogram and confirmed that the coronary artery fistula was indeed a long-standing finding in this patient. The cardiology team reviewed the patient and agreed that the coronary artery to pulmonary artery fistula was not the cause for patients’ current symptoms, and no further intervention was proposed.

Fig 2 & 3: Axial cardiac CT for calcium scoring (2a,b) performed in 2012 shows a similar aneurysmal sac with feeder vessels adjoining the pulmonary trunk (yellow arrows). The corresponding axial contrast enhanced CT images (3a,b) from his presentation this year is shown for comparison (green arrows).

Discussion:

Coronary artery fistula is defined as a precapillary connection between a branch of coronary artery and cardiac chamber, coronary sinus, pulmonary artery, or pulmonary vein[1]. In coronary artery fistulas, the communication can arise from the right coronary artery (50%), left coronary artery (42%) or both the coronary arterial systems (5%).[2] Though the majority of the patients are asymptomatic, some can present with chest pain, dyspnoea, and palpitations. Complications include pulmonary arterial hypertension due to the establishment of a left-to-right shunt and aneurysmal formation. Coronary artery steal phenomenon may be a theoretical risk in these patients, especially those with moderate to severe disease, for which some authors have advocated invasive FFR to assess the hemodynamic significance.[3]

Though in literature, treatment options for closure of fistula are described either by a surgical or percutaneous approach, nevertheless, there is no consensus on management strategies for coronary artery fistula.[4] In asymptomatic cases with no features of pulmonary artery hypertension or RV dysfunction, a conservative approach is wise. The case highlights the fact that even in the presence of multiple coronary artery fistulas and aneurysm formation, it would be safe to follow up in asymptomatic patients even for several years.

Questions:

- Which is the most common drainage site for coronary artery fistula?

- Left ventricle and atrium

- Right ventricle and atrium

- Pulmonary artery

- Superior vena cava

- Coronary sinus

Answer: II. Right ventricle and atrium

The right ventricle is the most common drainage site (41%), followed by the right atrium (26%), pulmonary artery (17%). The left ventricle, left atrium, coronary sinus, and superior vena cava are rarely involved.

- Which of the following are complications of coronary artery fistula?

- Pulmonary artery hypertension

- Cardiac failure

- Aneurysm formation

- Myocardial ischemia

- All of the above

Answer: V. All of the above.

In the case of large fistulas leading to significant left to right shunt, potential complications include pulmonary artery hypertension, cardiac failure, and aneurysm formation, which can rarely rupture. There is a theoretical risk of coronary steal phenomenon leading to myocardial ischemia in these patients.

- Regarding the treatment of coronary artery fistulas, which of the following statements are true?

- In asymptomatic patients, careful periodic evaluation and follow up may be suggested

- Transcatheter embolization of fistula is effective

- Surgical ligation in coronary artery fistulas with complex anatomy

- Antiplatelet and Prophylactic precautions for bacterial endocarditis

- All of the above

Answer: V. All of the above.

There is no consensus on management strategies for coronary artery fistulas. It would be wise to follow up asymptomatic patients carefully. Both endovascular and surgical approaches are effective in the treatment of coronary artery fistula, the decision of which depends on the anatomy of the fistula.

References:

- Schumacher G, Roithmaier A, Lorenz HP, et al. Congenital coronary artery fistula in infancy and childhood: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997;45(6):287–294.

- Nakamura M, Matsuoka H, Kawakami H, et al. Giant congenital coronary artery fistula to left brachial vein clearly detected by multi-detector computed tomography. Circ J 2006;70(6):796–799.

- Huang Z, Liu Z, Ye S. The role of the fractional flow reserve in the coronary steal phenomenon evaluation caused by the coronary-pulmonary fistulas: case report and review of the literature. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020 Feb 3;15(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13019-020-1073-x. PMID: 32013986; PMCID: PMC6998067.

- Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;139:e698–800.