Dr. John Dreisbach, Glasgow Royal Infirmary

Introduction

The term acute aortic syndrome covers a spectrum of life-threatening emergency conditions of the thoracic aorta, including dissection, intramural haematoma and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer. The potential acute complications are severe and diverse. The clinical manifestations are often non-specific and overlap significantly with other more common conditions requiring essentially the opposite treatment, most frequently acute coronary syndrome and pulmonary embolism. The best chances of survival depend on a rapid and accurate diagnosis (or indeed exclusion), usually by CT angiography and ideally cardiac-gated to minimise motion artifact.

Questions

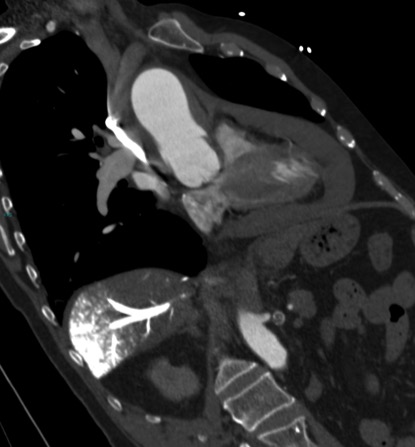

Review the single image below (a coronal-oblique reconstruction of a CT angiogram) and address:

- The type of acute aortic syndrome present

- The Stanford classification

- The major complication that has occurred

- The signs that this major complication is life-threatening

Answers

1. Acute intramural haematoma of the ascending aorta

There is an area of eccentric high-attenuation lining the wall of the ascending aorta, without discernible enhancement, consistent with an acute intramural haematoma.

2. Stanford type A

The Stanford classification of aortic dissections aids decision-making for management and also broadly applies to intramural haematomas. Type A dissections involve the ascending aorta and should be managed surgically whereas type B dissections classically commence distal to the left subclavian artery and should be managed medically.

The Stanford classification system is not without many important exceptions and caveats, but is generally useful and routinely employed in both clinical practice and research.

3. Large haemopericardium

There is a large pericardial collection of high attenuation consistent with acute haemopericardium, in this case due to rupture of the intramural haematoma of the ascending aorta.

Haemopericardium is the commonest complication of both type A aortic dissections and intramural haematomas and the most frequent cause of death in the acute setting, the mechanism of which is described below.

4. Cardiac tamponade (also known as pericardial tamponade), in this case evidenced by a large volume of relatively undiluted intravenous contrast material in a dependent position within the hepatic veins of the right liver lobe

The accumulation of fluid (in this case haemorrhage) into the pericardial sac, which is lined by a stiff fibrous capsule, transmits pressure onto the underlying heart. This can cause compression and reduced filling of the cardiac chambers, resulting in reduced cardiac output and obstructive shock.

The slow accumulation of fluid may allow time for the pericardium to stretch and accommodate relatively large-volume effusions before causing hemodynamic compromise. However, only a small volume (100-200 ml) of rapidly accumulating pericardial fluid may be required to produce obstructive shock. Unfortunately this patient suffered the worst of both – the rapid accumulation of a large pericardial collection.

In this patient, intravenous contrast was injected into an upper limb vein and undiluted contrast is seen in transit in the SVC. A large volume of undiluted intravenous contrast has travelled down the SVC, bypassed the right atrium, refluxed down into the IVC, and produced a striking appearance by accumulating in a dependent position within the hepatic veins and venous tributaries of the right liver lobe. The reflux of intravenous contrast into the IVC and dilated hepatic veins are key CT signs that the right heart is failing to fill with venous return and in this case represents severe cardiac tamponade at the time of the examination.

References

- Multidetector CT of aortic dissection: a pictorial review. McMahon MA, Squirrell CA. RadioGraphics 2010;30(2):445–460. http://pubs.rsna.org/doi/full/10.1148/rg.302095104

- Recommendations for accurate CT diagnosis of suspected acute aortic syndrome (AAS)—on behalf of the British Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (BSCI)/British Society of Cardiovascular CT (BSCCT). Varut Vardhanabhuti, Edward Nicol, Gareth Morgan-Hughes, Carl A Roobottom, Giles Roditi, Mark C K Hamilton, Russell K Bull, Franchesca Pugliese, Michelle C Williams, James Stirrup, Simon Padley, Andrew Taylor, L Ceri Davies, Roger Bury, and Stephen Harden. The British Journal of Radiology 2016 89:1061. http://www.birpublications.org/doi/abs/10.1259/bjr.20150705