Authors: Samer Alabed1, Boshra Edhayr2 and Annette Johnstone3

1 Radiology Registrar, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals

2 Radiology Registrar, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

3 Consultant Cardiothoracic Radiologist, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

In March 2021 this 72yo Asian female was admitted acutely with a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation with fast ventricular response. She was started on oral beta blockers, anticoagulated and discharged home. A fortnight later, she was readmitted with increasing breathlessness, and her rate was well controlled at this time.

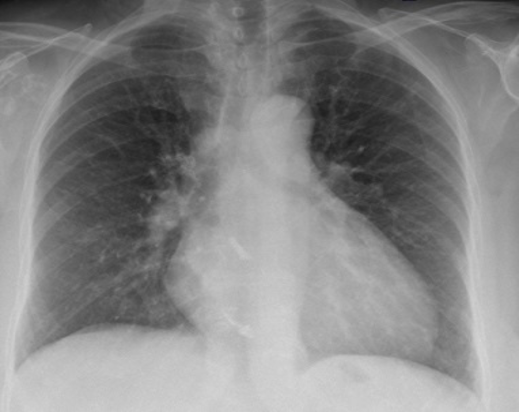

A chest x-ray demonstrated cardiomegaly with upper lobe diversion but no overt pulmonary oedema (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chest x-ray showing cardiomegaly. A comment was made about calcification in the right hilum and the heart

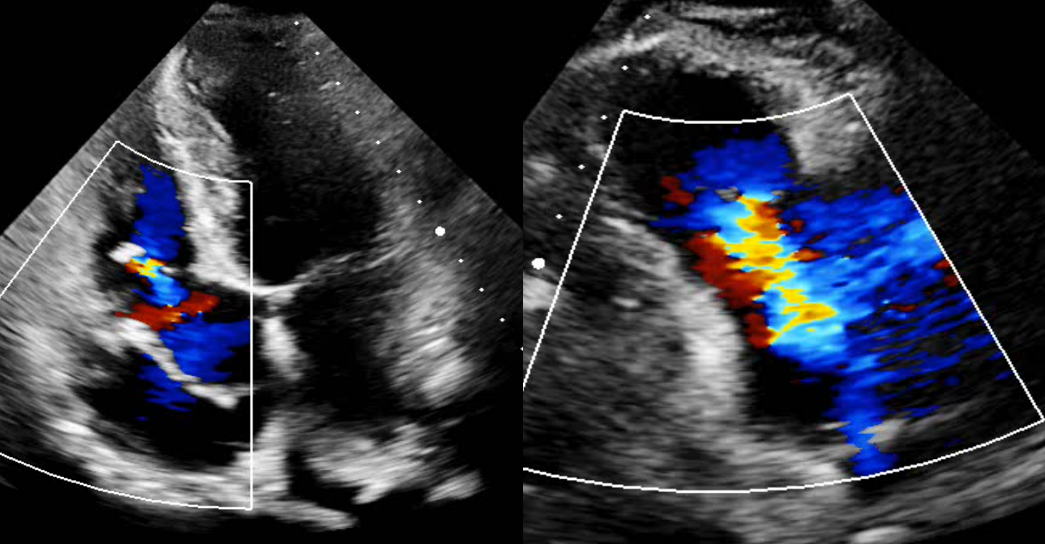

An echocardiogram was subsequently performed which showed normal left ventricular function with septal flattening and dyssynchrony. The right ventricle was mildly dilated with mildly impaired longitudinal function (TAPSE 14 mm). There was tethering of the anterior tricuspid valve leaflet and complete failure of coaptation of the tricuspid valve, resulting in severe tricuspid regurgitation (Figure 2). There was no significant pericardial effusion.

Figure 2: Echocardiogram demonstrating significant tricuspid regurgitation on the parasternal long axis right ventricular inflow view (right panel). On the apical four chamber view in the left panel, we can see an abnormal structure within the RA attached to the TV leaflet, which was considered to be a prominent Eustachian valve

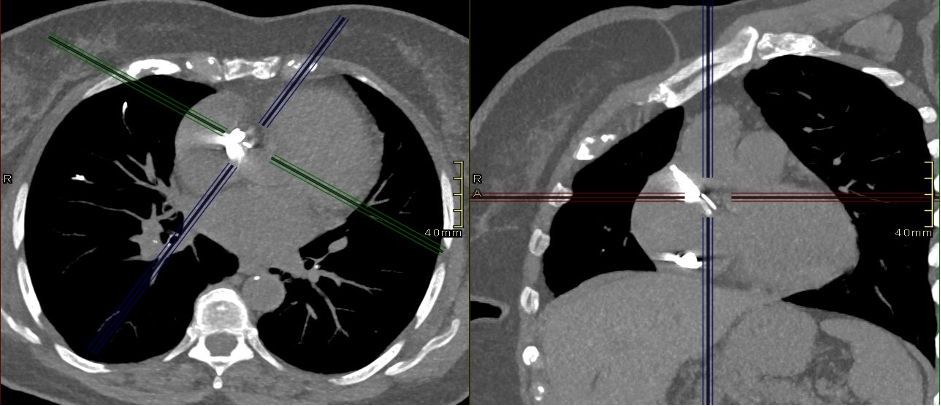

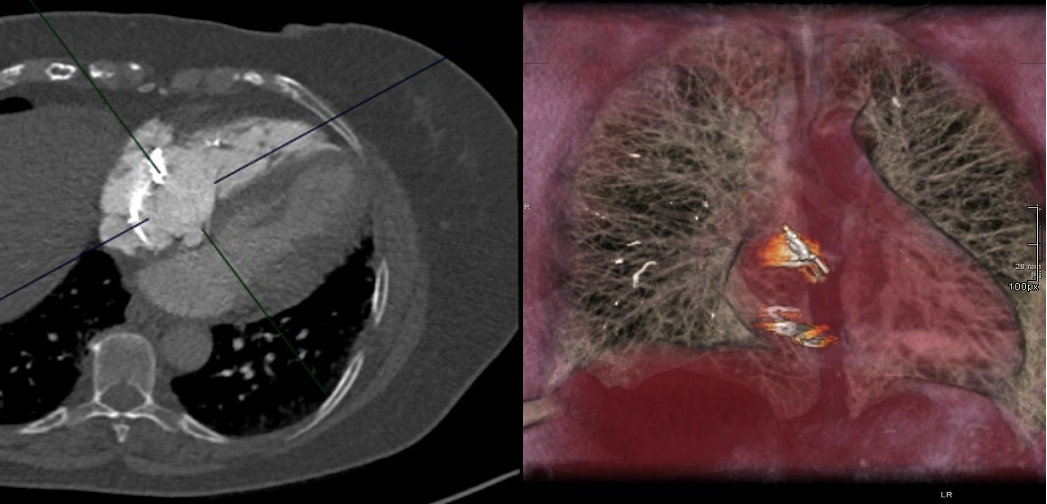

Subsequent HRCT (Figure 3) and CTPA (Figure 4) did not identify an acute pulmonary embolism. However, abnormal high-density material was identified within the right atrium and right atrial appendage with similar material noted within the right upper lobe pulmonary artery and subsegmental divisions of the pulmonary tree. The highly attenuating material within the pulmonary tree demonstrated a tubal and branching configuration. There was no evidence of cardiac perforation and no significant pericardial effusion. Appearances were thought to be compatible with iatrogenic embolization.

Figure 3: HRCT showing high density material in the right atrium. The full CT scan can be accessed through this PACSbin link

Figure 4: CTPA and 3D reconstruction showing high density material in the right atrium and pulmonary arteries (image on the right). The full CT scan can be accessed through this PACSbin link

Reviewing her past medical history, the patient had undergone spinal instrumentation and bilateral knee replacement surgery within the previous year. Interestingly, as her mobility improved, she became more short of breath. A diagnosis of cement embolization was made.

The case was discussed with the regional pulmonary hypertension unit who did not feel pulmonary endarterectomy would be of benefit to this patient. She is currently better, remains anticoagulated and is under regular outpatient review. At the time of writing, she is awaiting surgical discussion regarding the possibility of surgery to remove the material within the right atrium and potential intervention to the tricuspid valve.

Discussion:

Right heart and pulmonary cement embolism is rare and most commonly seen post embolization of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) following vertebroplasty procedures or rarely hip replacements. Fresh semi-liquid PMMA can extravasate into the vertebral veins and migrate to the right atrium via the inferior vena-cava. Patients are frequently asymptomatic and cement embolization is usually an incidental finding detected on chest x-ray or cross-sectional imaging. However, very rare cases of fatal cardiac perforation following cement embolization to the heart have been reported.

Treatment options vary, depending on the presentation and symptoms of the individual patient and range from observation and supportive treatment to anticoagulation or embolectomy.

Questions

1. What other types of pulmonary embolism do you know?

Answer: Acute / Chronic thromboembolism, Septic, Fat (trauma), Tumour, Amniotic fluid

2. What is the risk of cement pulmonary embolism after vertebroplasty?

Answer: 5%-7%

3. Which anatomical variants can be found in the atria and can mimic pathology on imaging studies?

Answer: Prominent Eustachian valve, Chiari network, and prominent Crista terminalis in the right atrium; prominent Coumadin ridge in the left atrium; lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum.

Acknowledgment:

We thank Dr Dominik Schlosshan (Consultant Cardiologist) for providing the echocardiogram images.

References

- D’Errico, Stefano, Sara Niballi, and Diana Bonuccelli. 2019. “Fatal Cardiac Perforation and Pulmonary Embolism of Leaked Cement after Percutaneous Vertebroplasty.” Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 63 (April): 48–51.

- Skjølsvik, Eystein Theodor Ek, Tor Steensrud, Øystein Dahl-Eriksen, Lars Uhlin-Hansen, and Per Ivar Lunde. 2015. “Cardiac Perforation Caused by Cement Embolus after Total Hip Replacement.” Circulation 132 (11): 1047–48.

- Zhang, Yi, Xinmei Liu, and Hongsheng Liu. 2022. “Cardiac Perforation Caused by Cement Embolism after Percutaneous Vertebroplasty: A Report of Two Cases.” Orthopaedic Surgery, January. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.13192.