Submitted by Dr Michelle Mak

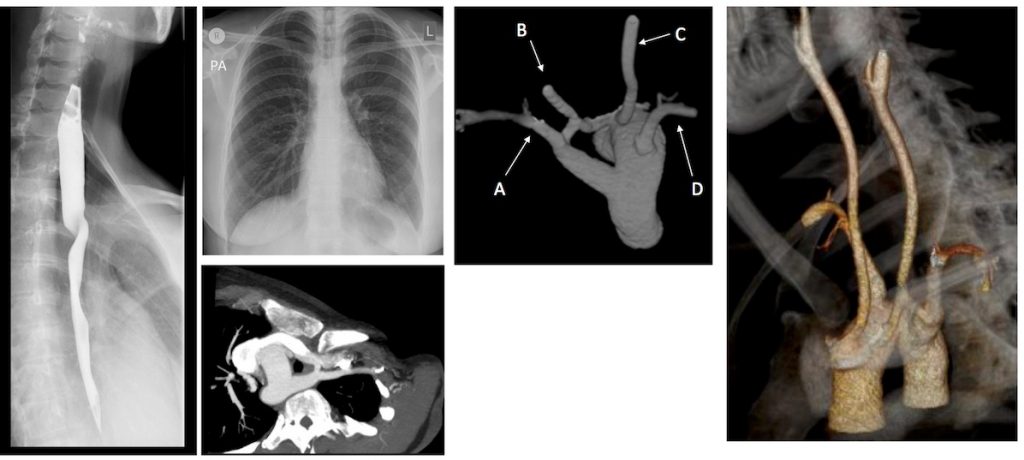

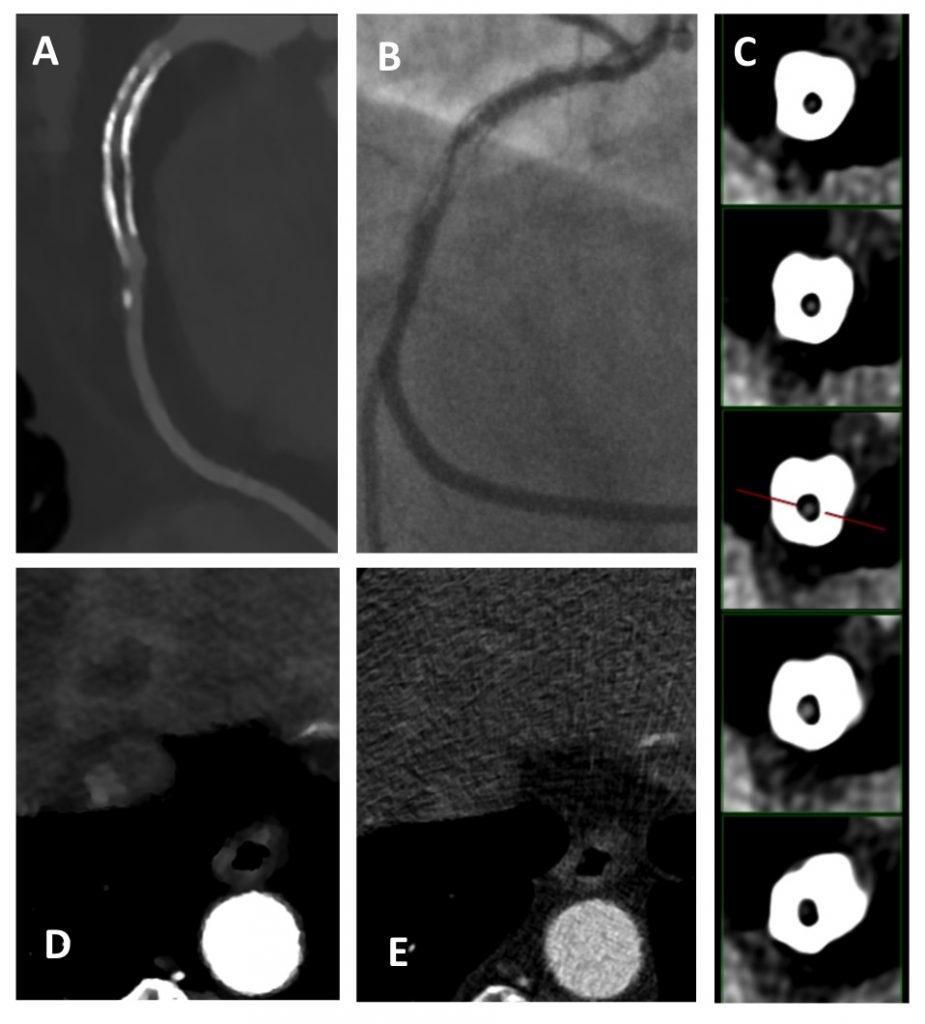

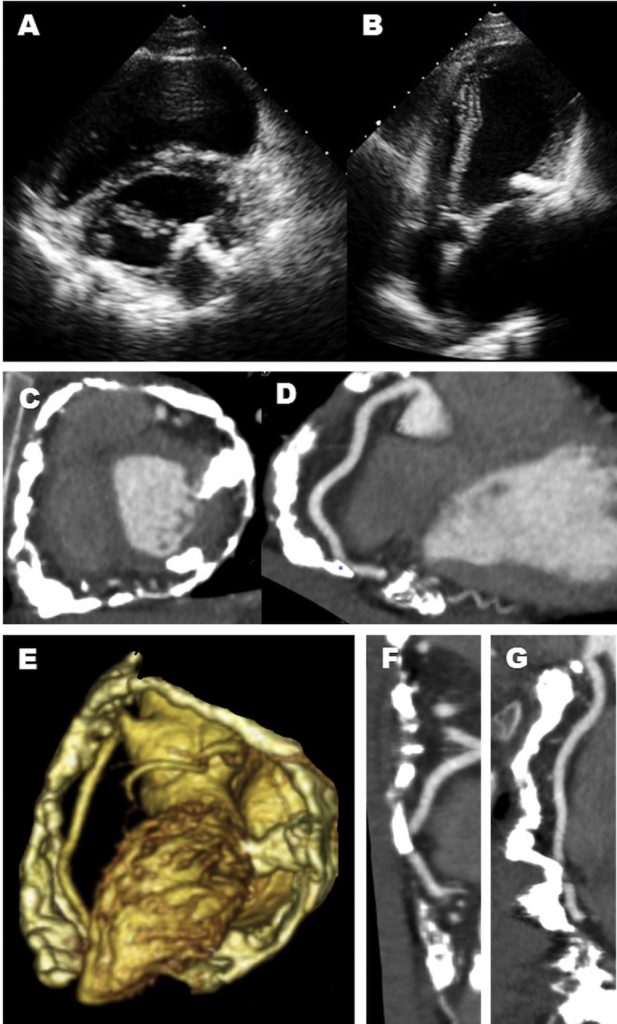

A 6 years old boy presented with swallowing difficulties. His chest radiograph is as shown. A barium swallow showed a posterior indentation, and a CT was requested.

Questions:

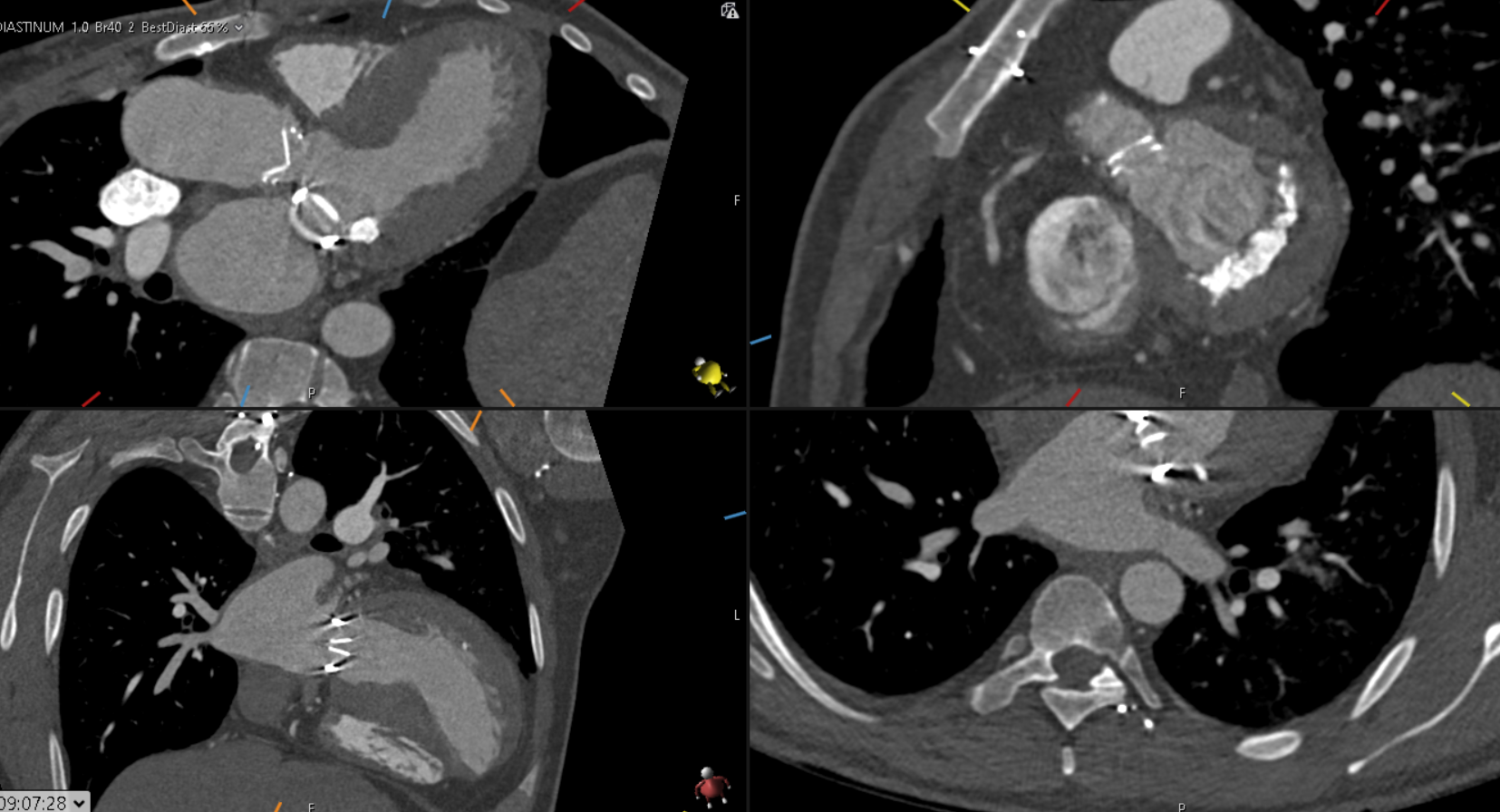

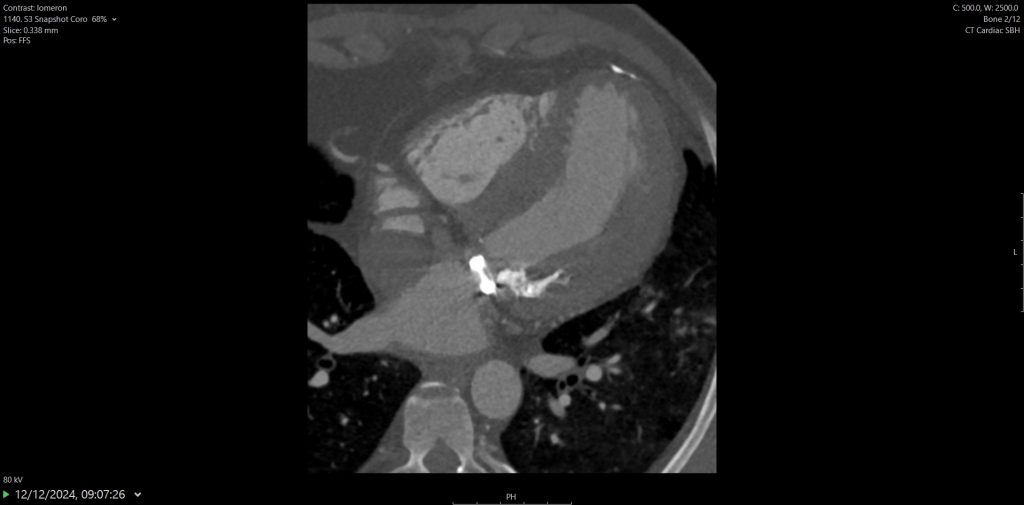

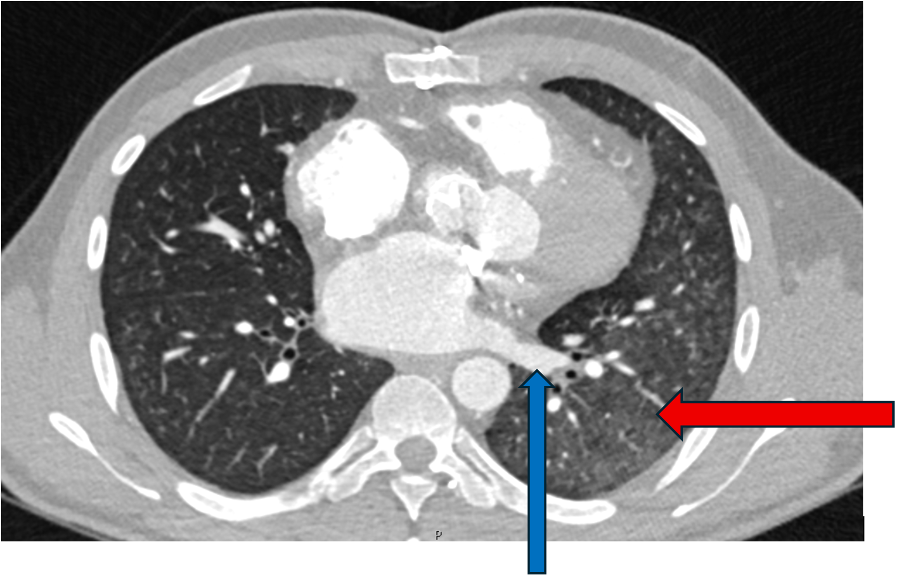

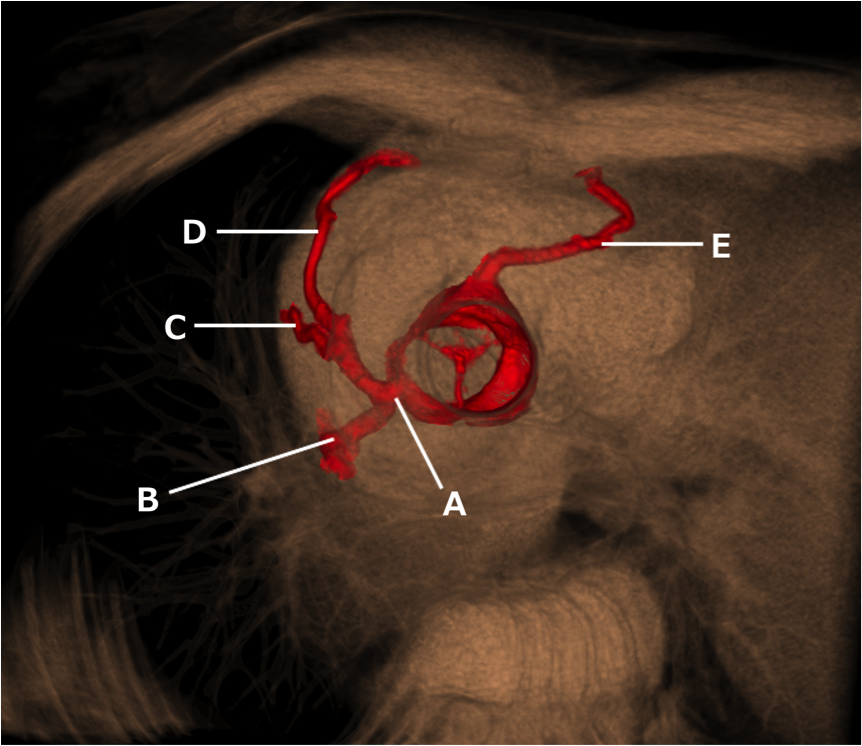

- Given the MIP MPRs, name the arrowed vessels A-D.

- What is this vascular anomaly?

Answers:

- A: Left subclavian artery (LSCA).

B: Left common carotid artery (LCCA)

C: Right common carotid artery (RCCA)

D: Right subclavian artery (RSCA).

2. Right aortic arch (RAA) with aberrant LSCA.

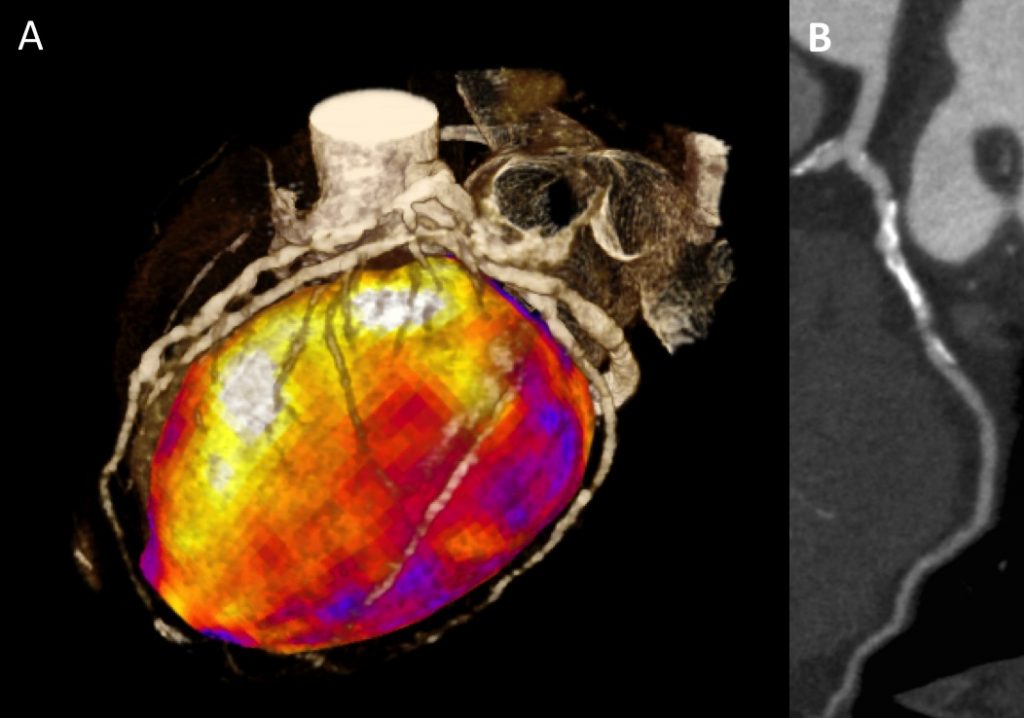

There are multiple arch anomalies, and they can be detected prenatally on foetal ultrasound, and postnatally with both ECHO and cross sectional imaging. A vascular ring typically encircles the trachea and oesophagus completely. RAA is present in 0.05% of the population. Based on the embryonic double aortic arch model, a RAA with aberrant LSCA is due to an interruption between the LCCA and LSCA. The first branch of the arch is the LCCA, followed by the RCCA and RSCA. Lastly, the LSCA is aberrant. If the LSCA origin is dilated, it is known as Kommerell’s diverticulum. The ring is commonly completed by a left ligamentum arteriosum, which could be treated by surgical ligation.

The second commonest pattern of RAA exhibits a mirror image branching pattern, with the left brachiocephalic artery arising first, followed by the right common carotid and right subclavian artery. It is commonly associated with congenital heart diseases and is asymptomatic.

References

- Donnelly L, Fleck R, Pacharn P et al. Aberrant Subclavian Arteries: Cross-Sectional Imaging Findings in Infants and Children Referred for Evaluation of Extrinsic Airway Compression. AJR:178, May 2002

- Türkvatan A, Büyükbayraktar G, Ölçer T et al. Congenital Anomalies of the Aortic Arch: Evaluation with the Use of Multidetector Computed Tomography. Korean J Radiol. 2009 Mar-Apr; 10(2): 176–184.